In the annals of automotive history, few names resonate with the thunderous roar of the race track quite like the Ford GT40. This sleek and powerful racing machine wasn’t just a car; it was a symbol of determination, engineering prowess, and an unyielding desire to conquer the world’s most prestigious racing circuits.

The GT40’s story is one etched in the asphalt of Le Mans, where Ford’s quest for glory collided with Ferrari’s dominance, giving birth to one of the most iconic rivalries in motorsport.

In the swinging sixties, Henry Ford II set his sights on defeating the perennial powerhouse, Ferrari, at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The GT40, born out of this audacious ambition, wasn’t just a race car – it was a technological marvel. With its low-slung profile, scissor doors, and thundering V8 engine, the GT40 was a force to be reckoned with, both in terms of performance and aesthetic appeal.

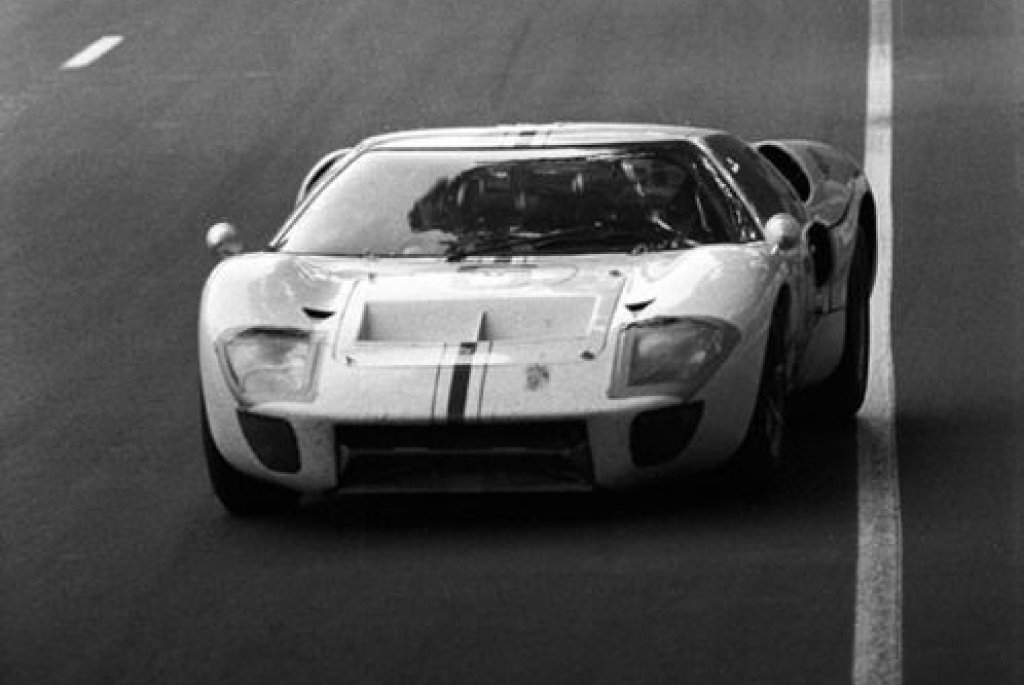

The clash between Ford and Ferrari at Le Mans in the mid-1960s was more than just a race; it was a battle of automotive ideologies, a duel for the hearts of racing enthusiasts worldwide. The GT40’s four consecutive victories at Le Mans from 1966 to 1969 stand as a testament to its engineering brilliance and the unwavering determination of the Ford team.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the legend of the GT40 continues to captivate audiences. “Ford v Ferrari,” directed by James Mangold, brings this riveting chapter of automotive history to the big screen, starring Christian Bale as Ken Miles and Matt Damon as Carroll Shelby. The film not only pays homage to the intense rivalry but also highlights the human stories behind the steering wheels, adding a layer of emotion to the roaring engines and screeching tires.

Beyond its historical significance and Hollywood glamour, the Ford GT40 has achieved classic status, cementing its place in the pantheon of automotive greatness. Enthusiasts and collectors alike cherish these racing legends, with their limited production numbers making them prized possessions on auction blocks around the globe.

As we delve into the world of the Ford GT40, we embark on a journey through time, tracing the tire tracks of triumphs, setbacks, and the enduring legacy of a car that not only conquered Le Mans but also etched its name in the collective memory of racing enthusiasts and cinephiles alike. Strap in, as we rev our engines and navigate the twists and turns of the Ford GT40’s remarkable journey – a journey that continues to leave an indelible mark on the fast-paced history of motorsports.

The Beginning

In the clear light of day, Ford’s decision to enter and, importantly, win the Le Mans 24 Hours was a seemingly outrageous idea. The company had been absent from official motorsport competition for over five years due to the American Automobile Association’s ban on factory participation in motor racing. Yet, Ford felt confident enough to challenge the top European manufacturers on their own turf.

At that time, Ferrari held a dominant position at Le Mans, securing victory for six consecutive years between 1960 and 1965. Initially, it seemed that the simplest way for Ford to win at Le Mans would be to acquire Ferrari and place a blue oval on one of its race cars.

This possibility almost materialized until Enzo Ferrari famously backed out of the deal at the last minute. Henry Ford II, infuriated by this, resolved to outdo Ferrari in its own domain. Consequently, Ford established a separate division called Ford Advanced Vehicles (FAV), leading to the creation of the Ford GT40.

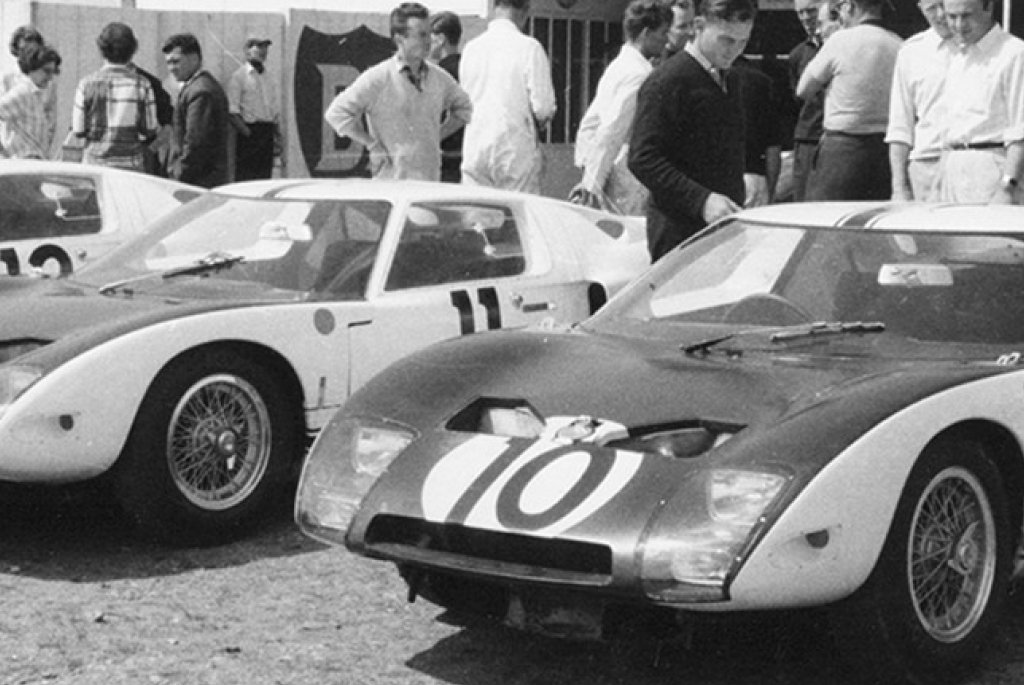

In a typical fairy tale, the narrative might unfold with Ford immediately dominating contemporary Ferraris, but success was not immediate. GT40s, right from the outset, demonstrated speed but also proved to be fragile. In its debut at Le Mans in 1964, all three GT40 cars retired—one due to a fire and the other two due to gearbox failures. Despite Ferrari achieving a clean sweep of the podium, there were some encouraging signs for Ford. Phil Hill set a lap record, and a GT40 led for the first hour or so.

Much effort was dedicated to refining the GT40 for the 1965 season, but it fell short. Despite initially running one-two, all six Ford cars had retired by the sixth hour, allowing Ferrari to once again dominate the podium.

However, Ford’s fortunes took a turn in 1966, as Henry Ford II finally achieved the coveted Le Mans victory. GT40s secured the first, second, and third positions, marking the beginning of Ford’s dominance. This success continued in 1967, 1968, and 1969, comprehensively putting an end to Ferrari’s reign at the event.

The Detailed Breakdown of Ford GT40

The development of Ford’s Le Mans contender began in late 1963 at FAV’s (Ford Advanced Vehicles) new headquarters in Slough. The high-performance team included key figures such as Ford’s Roy Lunn, Carroll Shelby, John Wyer (Le Mans winner with Shelby driving for Aston Martin), and Eric Broadley, whose Lola GT was considered groundbreaking.

As part of the collaboration, Broadley brought two Lola Mk6s, mid-engined race cars with Ford V8 engines that had already shown promise on the track.

The chassis underwent stiffening, and the 4.2-liter Ford Fairlane engine was upgraded to the lighter, 350bhp ‘Indianapolis’ version from the Lotus 29.

Extensive test sessions, often with Bruce McLaren at the wheel, focused on fine-tuning the suspension (double wishbones at the front, transverse links, and radius arms at the rear).

Wind tunnel tests using a 3/8th scale model led to modifications in the fiberglass body for improved aerodynamics, especially up to speeds of 125mph, which was the highest relative speed the wind tunnel could replicate.

After making its public debut at the New York Motor Show in April 1964, the GT40 (retrospectively known as the Mk1) underwent trials at Le Mans.

Jo Schlesser, behind the wheel, experienced the limitations of wind tunnel testing with a significant accident at 150mph on the Mulsanne straight. This incident highlighted instability at high speeds, leading to the hurried design of a rear spoiler for the upcoming Le Mans main event.

The Mk1 proved to be fast but fragile at Le Mans in 1964, facing further setbacks, including a disastrous showing in Nassau in December.

This led to a decision in Dearborn, Michigan, to relocate the program back to the US. Carroll Shelby took operational control, with Roy Lunn in charge of engineering.

Under Shelby’s leadership, the GT40, powered by the tried-and-tested 380bhp 4.7-liter Ford V8 from the Shelby American Cobras, achieved its first race win at the Daytona 2000 km in February 1965.

The car underwent numerous changes, including the use of lighter fiberglass, wider magnesium wheels, and modifications to enhance aerodynamics.

Despite these modifications, the 1965 Le Mans 24 Hours was a disaster for Ford. The Ferraris were faster during pre-trials, prompting the team to prepare two GT40X cars with the 7-liter 427 cubic inch V8. While incredibly fast, the lack of development affected both GT40 versions at Le Mans, leading to all Fords retiring before one-quarter of the race distance.

Undeterred, the team continued GT40 development. By mid-September 1965, significant changes to the body, suspension, fuel system, and brakes resulted in the new model, designated the MkII.

Ready for testing in the Dearborn wind tunnel, the MkII featured heavier-gauge metal, increasing weight and brake stress. Despite concerns about brakes and the gearbox, the team believed they had a winning car. Interestingly, MkIIs used four-speed manual transmissions, as the 7-liter engine’s torque made a five-speed gearbox unnecessary.

Eight factory cars were entered at Le Mans in 1966, and aside from a minor hiccup when Ford attempted to engineer a joint win for its two leading cars, it was a resounding success. The victory marked the culmination of three years of engineering, design, and research to develop both a winning car and team.

The success didn’t end there. A MkIII, fitted with the 4.7-liter V8, was briefly produced as a road car (only seven were made). To sustain the GT40’s success, an all-new MkIV was constructed for the 1967 Le Mans.

Ford aimed for more control over the project, bringing it in-house, with the new car designed by Ford and produced by the Ford subsidiary, Kar Kraft.

While retaining the engine and gearbox, it featured a more streamlined body and an entirely new chassis with improved crash protection. Only six MkIVs were built, and they participated in two races in 1967—the 12 Hours of Sebring and Le Mans—winning both.

The 7-liter V8 was effectively banned for 1968, as the Le Mans race organizer, the ACO, sought to reduce speeds. Nevertheless, thoroughly revised MkI GT40s equipped with the smaller 4.7-liter V8 secured overall victories at Le Mans in 1968 and 1969.

From the drawing board in 1963 to four Le Mans wins in just six years, the GT40 stands as one of the most revered endurance racers of all time. While it took Henry Ford II longer than he desired, it was indeed a remarkable achievement.